The Fall of The Russians

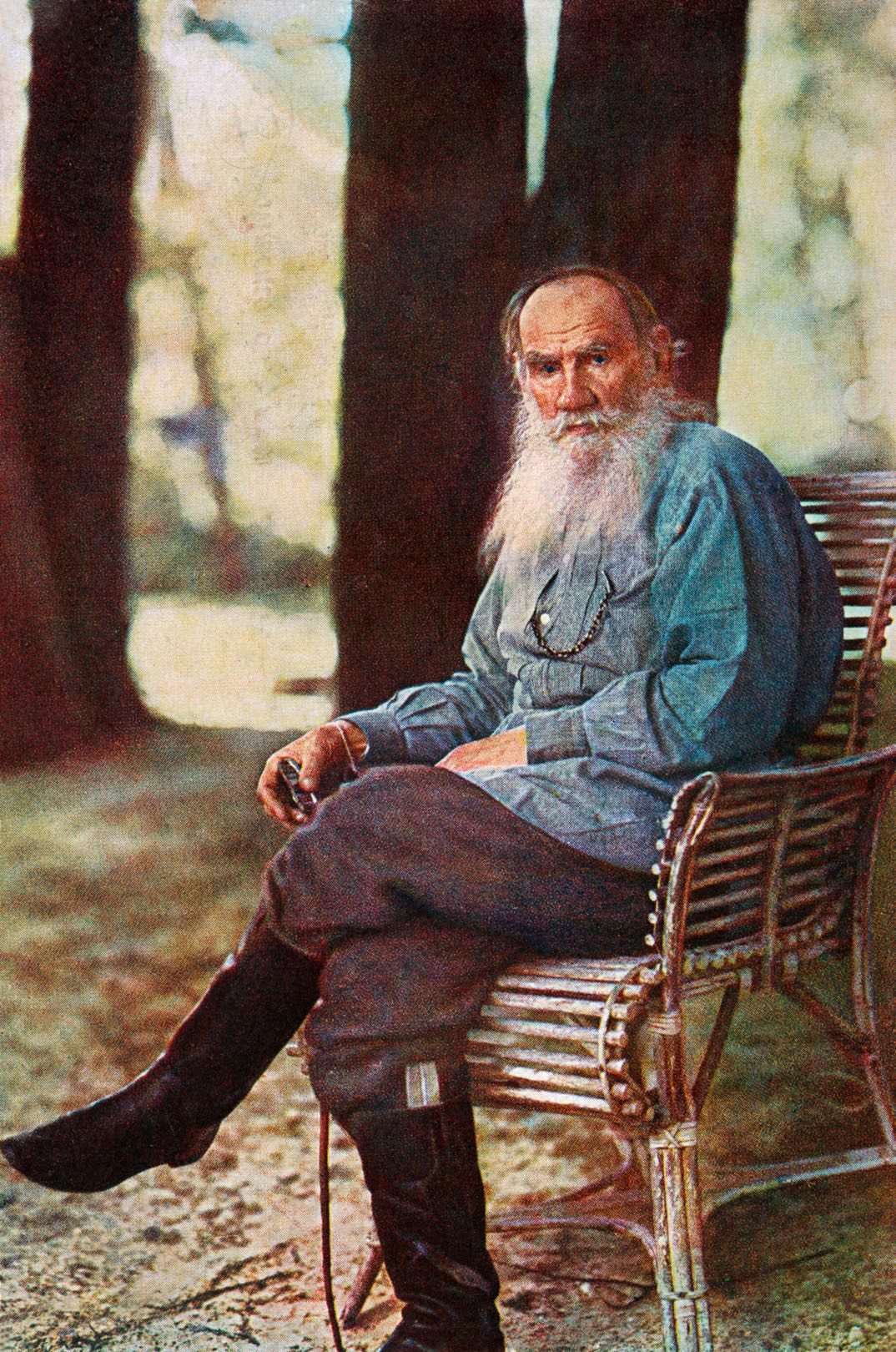

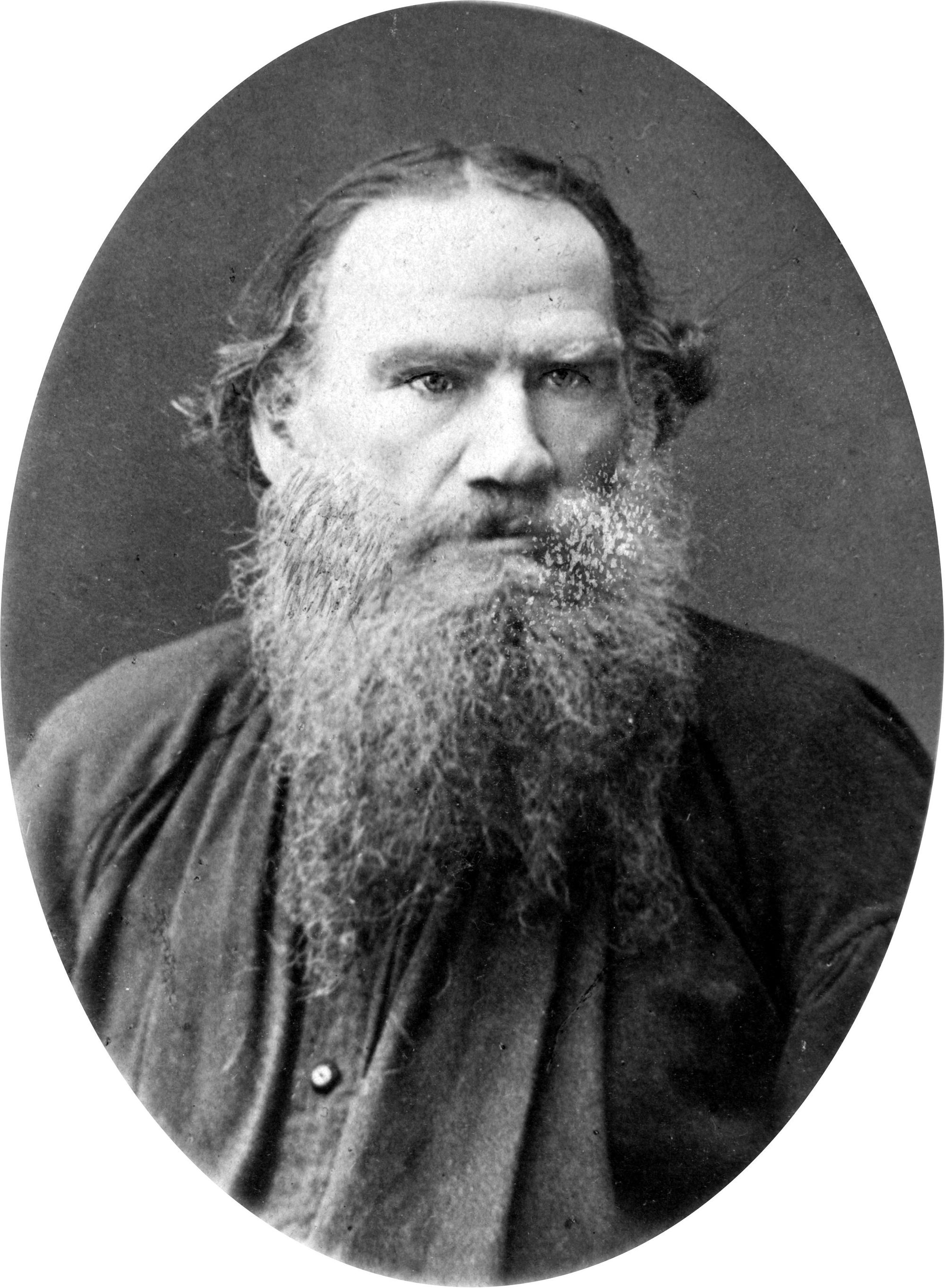

Leo Tolstoy is quickly falling out of favor with the modern audience. A new generation, defined by a short attention span and experiential outlook, threatens the longevity of his legacy as his work is pulled from classrooms and curriculum guides. Labeled out of touch, archaic, and even insane, Tolstoy is often misunderstood and misinterpreted in the academic setting. This essay attempts to combat a growing opposition to classic literature, higher thought, and philosophical concern, while highlighting the life of one of the most extraordinary men of the 19th century. With collected works amounting to over 90 volumes, Tolstoy was prolific, commenting extensively on the state, human nature, and most often, the society in which he lived. His ideas remain in relevance to this day, inscribed in works of fiction that parallel reality. Drawing from a difficult, conflicted childhood and adolescence, Tolstoy raised the novel to new heights and pushed the boundaries of language. One of the greatest writers in history, Tolstoy should be remembered because of his lasting contributions to literature, life of conflict , and steadfast moral and religious philosophy, advancing society and the human narrative.

A Varied Upbringing

Tolstoy was deeply influenced by the historical climate of the time. Angered by the injustice of government and constant inequality, people found answers in Tolstoy’s work, inspiring change. Born in 1828 in Yasnaya Polyana, Tolstoy grew up surrounded by western education and nobility. Amidst the global colonialism, scientific positivism, and religious mixing of the 19th century, Tolstoy desperately searched for understanding, gravitating towards philosophy at the age of fifteen. Additionally, Tolstoy wrote and lived during a period of great change in Russia. During the reigns of Alexander I and Nicholas II, Tolstoy experienced violence, social upheaval, and revolution, from the Crimean War to the abolition of serfdom to Bloody Sunday. At the end of his life, the Industrial Revolution swept through Russia, bringing the country into a global network of trade. Consistent throughout, however, was an oppressive state and decades of tradition. In this way, Tolstoy only becomes more impressive, able to succeed and question in an environment so against him.

The Price of Genius

Before becoming a worldwide novelist and moralist, Tolstoy lived the life of conflict that his stories embody. He was “one of the great rebels of all time, a man who during a long and stormy life was at odds with Church, government, literary tradition, and his own family”. During his childhood, he frequently moved between relatives, eventually settling in Kazan among high society. Early influences include his father’s death and his aunt, whose religious fervor would later drive Tolstoy’s extensive beliefs and thoughts on Christianity. Most surprising, perhaps, was Tolstoy’s lack of success in school. He dropped out of university and never received any formal training in writing, instead leaving home to join his brother in military service. During the long lulls between battles, Tolstoy began to write, drawing from his own experience in war, such as life in a Cossack outpost or the artillery barrages at Sevastopol. After leaving the service and becoming disillusioned with the aristocracy, Tolstoy returned home to found a school for peasant children, all the while writing in between. When his brother died, however, Tolstoy became obsessed with the inevitability of death, broken by the loss of his closest relative. Everything changed when he met his wife, Sofya Andreyvna Behr. Beautiful, intelligent, and strong willed, she was the perfect companion to his writing, propelling Tolstoy into his golden years of creation. With the support of his family and the beginnings of critical acclaim, Tolstoy wrote “War and Peace” and “Anna Karenina” all within the span of 10 years. Even Tolstoy himself remarked upon this period in his life with great happiness. However, as Tolstoy aged, his desire for true meaning in life consumed him, leading to the spiritual crisis that dominated the later part of his life. He fervently sought answers in Christianity, particularly Russian Orthodoxy, but was never satisfied. Instead, he returned to the faith of his youth, enlightened by fierce moral and religious convictions, as well as a desire for social justice. Before his death in 1910, Tolstoy helped the poor and wrote some of his best stories, including “The Death of Ivan Ilyich”, but also drove his family away, crazed by a higher calling. With global fame, literary acclaim, and a wealthy estate, Tolstoy had affected society forever. He never stopped questioning while he attempted to maintain a personal life of love and family. Yet, the price of genius took its toll on Tolstoy, presenting hardship, uncertainty, and dissatisfaction in his life. He should be remembered for his greatness as well as his struggles, and most importantly, his humanity and curiosity throughout his life.

Why His Work Still Matters Today

Tolstoy dedicated his life to the novel, redefining the constraints of literature as he deconstructs genre and defies feasibility. His work is dense, incredibly detailed, and at times slow. He is undoubtedly un-afraid in his description and intricacy, and his stories are always incredibly complex. Some consider actually reading Tolstoy to be an impossibility, a painful task. Yet, this perception betrays the meaning that Tolstoy intended. Tolstoy’s work is an experience, a journey through human thought and emotion. His climaxes are slow revelations, intended to mimic real life, where “Tolstoy's epiphanies feel true because they don't create immediate change”. Furthermore, his work is never a product of sole imagination. In War and Peace, possibly his most famous novel, Tolstoy expounds upon casualty, chance, and connection, weaving the story together with time and character . In over 1,358 pages, Tolstoy covers an extensive range of topics beyond the plot of his fiction, covering history, philosophy, and morality.

Subsequently, War and Peace is perhaps better known for its numerous epilogues and summations than the actual text itself. Often times these additions raise more questions than they do conclude a long and interminable story. Even Tolstoy himself only expanded the novel after writing at least half of it, proving how War and Peace was never intended to be fully understood or dissected, instead serving as a repository of thought. Nonetheless, Tolstoy’s work remains in modern relevancy. Even now, society raises questions about the role of the individual in the machinery of history and how the past can directly affect the future, how “no individual is more than one node in a vast and unpredictable web of interacting forces, conscious and unconscious, contingent and necessary” as he explains (Bram 7). Tolstoy attempts to find his own understanding to these questions, preaching to the importance of private happiness and the denunciation of the state with eloquence and prose. As his characters experience tragedy and triumph, Tolstoy appeals to the fundamental human nature of the reader, evoking emotion, empathy and at times frustration in his audience, while redefining the modern novel.

More Than Just A Novelist

Tolstoy played a principal role in not only the literary realm, but in the advancement of moral and philosophical thought of the time, presenting new ethical frameworks far ahead of his time. These beliefs, including his enduring fear of death, were an important precursor to the existentialist movement and even inspired a group of devotees known as Tolstoyans, appealing to “many individuals who were disillusioned with modern industrial society and the politics of the time”. Core to his Christian idealism is a complete criticism of the state. In “My Confession”, he targets the government as the proprietor of violence in society and as a deceitful institution with no place in an anarchist society . In fact, “Tolstoy denounces not just war but also law and the economy as violent and enslaving, all under the ruthless mechanical supervision of the state machine,” and therefore exhausting the power of reason.

However, Tolstoy still acknowledges the inevitability of human nature, such as the tendency of armed men to use their weapons or the natural product of economic exploitation. In this way, Tolstoy’s ethical and religious belief is deeply rationalistic and straightforward. He followed strict rational doctrine and always defended his arguments under scrutiny, doing so “consistently and with great vigor”. He preached complete non-violence, arguing that “violence is never justifiable, because it always causes more violence further down the line” providing the basis for the later work of pacifists such as Mohandas Gandhi. He maintained an absolutist interpretation of the law, guided by fierce moral principles. Evidently, Tolstoy’s political and social thought was revolutionary for the time period, presenting reality in a new light, threatening religion, the state, and the very threads of society.

Timeless, Poignant, and Relevant: Tolstoy in the 21st Century

Tolstoy should be remembered for his lifelong commitment to language, knowledge, and rationalism. Throughout his career, he raised the novel to new heights, engrossing readers in “the Zen of Tolstoy” (Bram 1). War and Peace remains possibly the greatest novel of all time and “much of it has not lost relevance since he first wrote it more than a century ago,” serving as a testament to his legacy and constancy. Tolstoy strived for perfect understanding, straddling the line between rational thought and faith. Yet, in his tireless search he found imperfection; in history, in society, and in government, and the contradiction in his own beliefs. After his death, his followers, dedicated to his memory, continued his curiosity as they “lived through miserable days and sleepless nights tormented by the simple question of 'what to do?'” (Alston 7). This question remains in perpetuity, relevant to the modern generation and the young students who face life in front of them. While the answer might never come, Tolstoy opened the doors to human discovery and intellectual curiosity, paving the way for a modern era of thought.